When I first joined Facebook (towards the end of high school), I was very reluctant do so. I had witnessed others around me use various social media and networking sites — think MySpace and MSN Messenger — only for the most banal conversation. Chats that I saw consisted of nothing more than ‘What’s happening?’ and ‘LOL’. It just wasn’t for me.

The thing that finally convinced me to join was an exchange trip to Germany. I saw the value of remaining connected with friends overseas and understood that it would be useful to chat with local friends as well. Facebook was much simpler then, with a cleaner interface that focused more on actually seeing what your friends were doing and saying. As I entered university, undertaking a degree in communication, I joined even more social networks, hungry to understand more of these digital platforms.

Over the past few years, I shed almost all of those networks. Some were fun; some failed. In the end, I saw them for what they were: a waste of my time. Facebook was always the one that I wanted to delete the most, as I saw it transform into a bloated mess of advertisements and algorithmically-suggested posts.

Whenever I came close to deleting my account, I hesitated. I didn’t want to stay but my many of my friends and photo uploads were there. It seemed such a waste to discard a part of my digital history. Perhaps most importantly, I first spoke to my fiancée Natasha through Facebook, using Messenger. I eventually settled for account deactivation, keeping the account in a state of distant hibernation for quite some time.

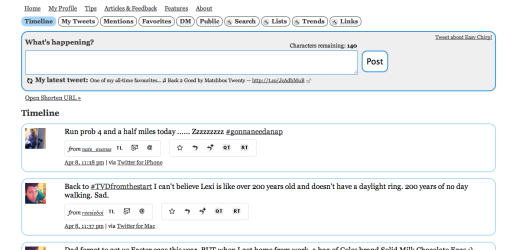

With the recent news about Facebook’s data privacy issues with Cambridge Analytica, my frustration with the company and its practices had flared up again. Out of the blue last weekend, Natasha notified me of the Twitter conversation below.

This finally pushed me over the edge. If Elon Musk, a man who runs several companies with millions of Facebook followers, could delete such an account without a moment’s hesitation, then why couldn’t I? I went straight to my study, visited Facebook on my Mac, downloaded my personal account archive and requested full account deletion. Not long afterwards, I received an email saying that it would be deleted within 14 days. Now I’m simply waiting for it to be deleted. They must be snapping the hard drives by hand.

This story of mine is in no way extraordinary, however I feel that it’s useful to share, particularly after spending approximately a decade on the network. Regardless of your level of devotion to Facebook, if you have an account, then you are in some way feeding their machine. The company has been either unwilling to change or is in complete denial that it needs to do so.

Other networks have their own issues too. I love to use Twitter and see it as the best example of social media that can democratise global conversation; it can connect you with people whom you’ve never met in person and (hopefully) expose you to new ideas. The company still has a long way to go to deal with issues of online abuse and trolls, however, and I look forward to seeing them actually do something about it.

For the moment, Instagram is safe on my iPhone, as it seems to have some degree of managerial independence from its parent, Facebook. My finger, however, is always hovering over the button.

Companies that hoard people’s data and use it inappropriately should be paying very close attention to what is happening right now.

If you have ever considered deleting your account, then ask yourself: why haven’t you done it yet? Question the value that it brings to your life. Do you just scroll aimlessly? Do you wonder why you connected with people with whom you never actually speak or meet in person? Are you comfortable with the use of your private information to deliver ‘personalised’ ads?

The time has come to delete Facebook.