Yesterday, I had the pleasure of visiting the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney to check out the exhibition Interface: People, Machines, Design. Featuring both retro and recent consumer products (primarily from Apple, IBM and Braun), the exhibition focuses on the significance of consumer products in our lives today. More importantly, it illustrates the strong emotional connection that we develop with such products, due to the marriage of effective industrial design, iconography and typography. Ultimately, for a technological product to be successful, it must tell a story and be clear, simple and accessible to as many people as possible.

My wonderful girlfriend, Natasha, was kind enough to attend with me and watch me giggle with glee as I surveyed the numerous exhibits. My Apple zealotry has (of course) infiltrated her life, and I’m pleased to say that she enjoyed it as well. 🙂

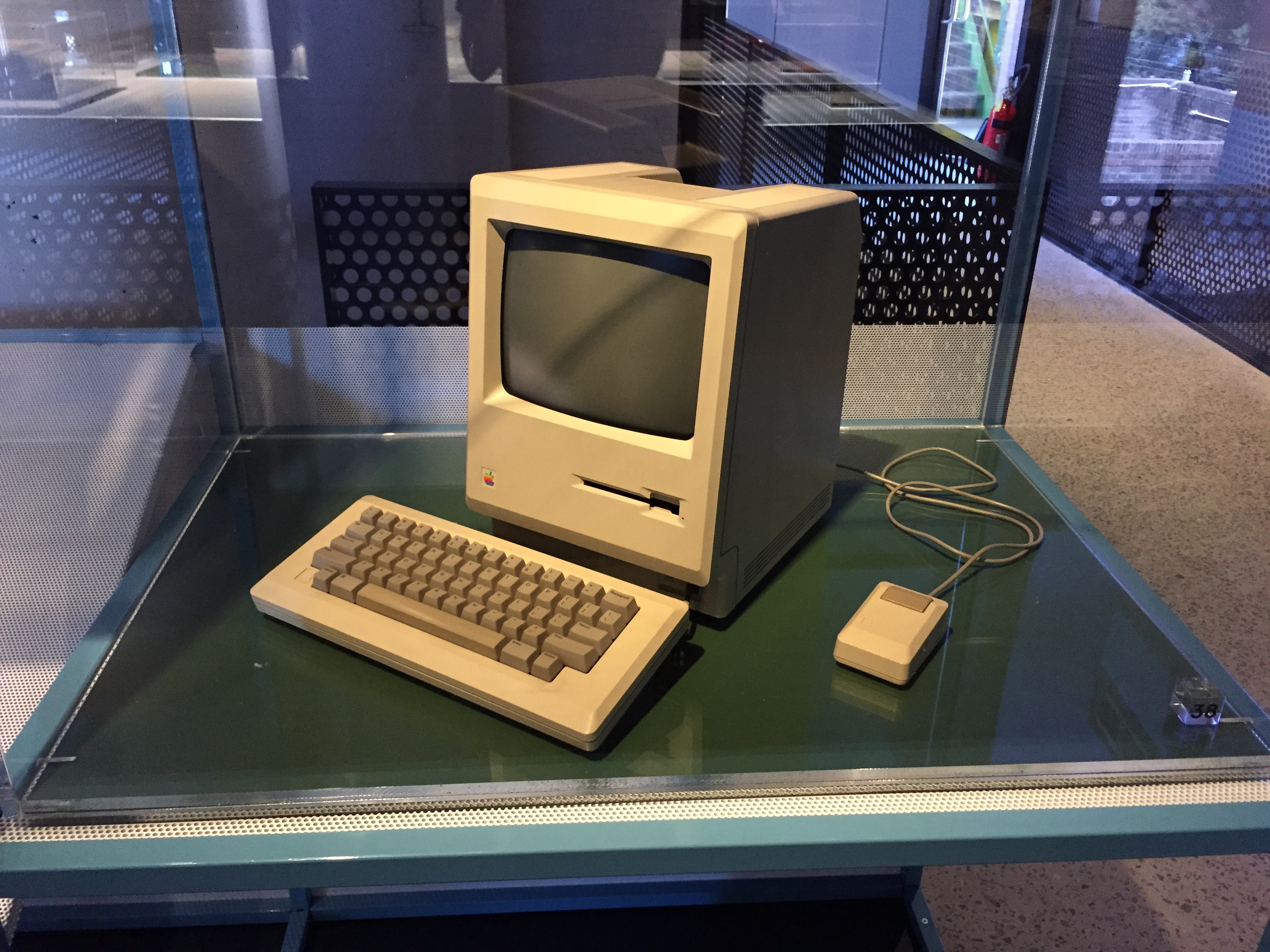

As we toured the rather small exhibition, it became clear that the space itself was constructed to reflect the products featured; everything was minimalist, considered and ordered chronologically, showing the influence of early democratic design by legends like Braun’s Dieter Rams through to today’s ubiquitous smartphones and tablets.

It was fantastic to see the history of Apple laid out so well, obviously by people who understand the significance of the personalities involved beyond Steve Jobs. Jony Ive, Helmut Esslinger, Susan Kare… all were mentioned appropriately.

I would highly recommend this exhibition to just about anyone. If you own a smartphone (which you do), it’s amazing to look back and appreciate the immense change that occurred during the 20th century, and the change that continues to occur every day. We take our digital products for granted, along with the empowering connectivity they facilitate. There has never been a better time to be alive.

Rather than bang on forever, it’s best to give you some links to find out more.

To view more photos of the included products, head over to my Flickr page.

For even more information about the exhibition and the specific products, visit the museum’s website.